All red flowers

an exhibition and a poem-score

I wrote some months ago about a book I had produced as part of a residency at Holocaust Centre North. That book is now out, and is on sale at the museum and on their website, and some independent bookshops, and you can read an extract from my ‘notes’ at the end of it here. There will be a proper launch at the Warburg Institute in November, where I’ll be talking with the writer-in-residence of last year, Tom Hastings. In June there was an exhibition of the ten artists and three of the four writers from the first three years of the residency programme, at Sunny Bank Mills in Leeds. The exhibition is over, but I’ve just been sent the documentation and wanted to write something quickly about it.

When I arrived to install I was struck immediately by the space, the first floor of a former textile mill, which I had only seen in photos and as a mock-up. It was huge, and lovely, simultaneously austere and busy: tall windows, the light changing across the day and with the weather, a few of which had been blacked out with considerable effort to allow for projections; a rough, uneven wooden floor, bare brick, white pillars, an old loom. Light, sound, texture, and a very insistent sense of its own former purpose, its identity, as part of a geographically specific history, sat alongside and in some ways intruded, I think to the disquiet of some of the artists, on the works.

Others fought back, working against the space, particularly Ariane Schick, who cut and laid down a large round golden yellow carpet in defiance of the layout demanded by the pillars, as part of her installation, book and animation, Manny:

Holocaust Centre North’s tagline is ‘a global history through local stories’ and its archive focuses on the collections of survivors and refugees who settled in the North of England – several of whom were involved in the textile industry – and the venue illustrated this approach well, as it did the brief of the residency programme, which invited participants to explore how the past informed present actions, and to work with aspects of the centre’s collections that had present relevance. When I got to Sunny Bank Mills I was a little afraid that the works would look lost in the space, but I thought we filled it nicely; that some of that filling was harmonious – Hannah Machover’s display table of etchings, for instance, which looked as though it had been left there in the early twentieth century – and other parts involved small tussles for dominance, was all to the good.

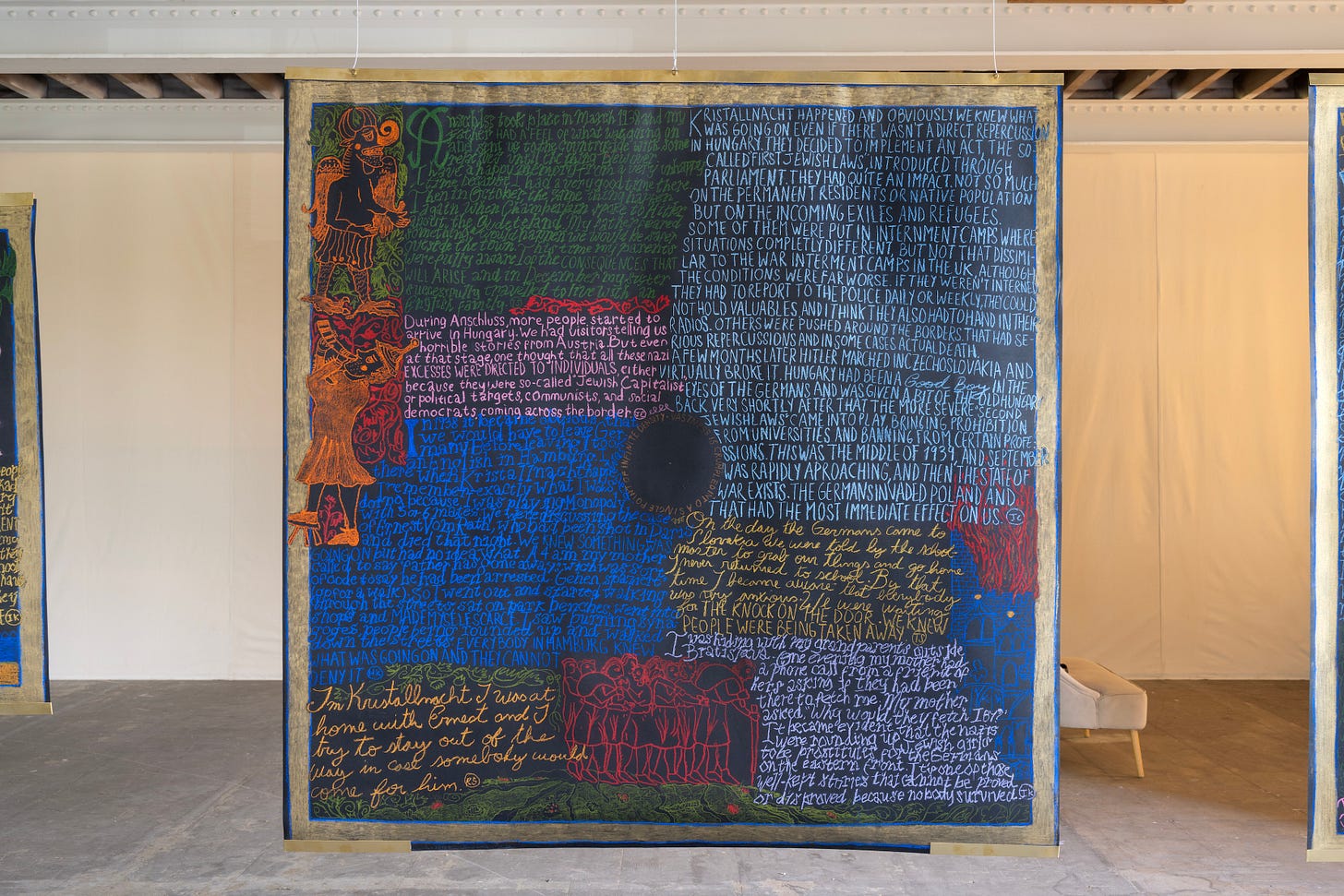

The second thing that struck me when I got there was the seven drawings of Chebo Roitter Pavez laid out across the rough wooden floor ready to be hung, coloured pastel on large sheets of black paper – visible here behind Hannah’s work in the photo above. The works combined snippets from the testimony of survivors with motifs from medieval Jewish manuscripts in rich colours and gold:

Chebo was in the third year of the residency and I’d neither met him nor seen anything of his work, and so it came as a kind of shock. For the first time I saw how much my idea of what this kind of work looked like – work specifically about the Holocaust, but perhaps more generally about atrocity, historical or present – had been limited to particular conceptual and aesthetic modes: fragments, ruins, visible breaks and gaps; austerity, modesty, restraint, whites and blacks; silence, an emphasis on the unspeakable; fidelity and authenticity of reproduction; intellectualism. That’s not what all of the work in the exhibition looked like or appealed to by any means, but it was only on seeing the colours and the gold, the excess, the polyphony and richness of Chebo’s drawings that I was able to understand that I hadn’t before known that that was possible. It’s not even that I thought they were good, exactly, although it’s certainly not that I thought they were bad – they were too novel, to me, for me to begin to evaluate them in those terms. What struck me was the challenge that this novelty posed to me, a whole way of making art that I hadn’t known about and wouldn’t have dared to do.

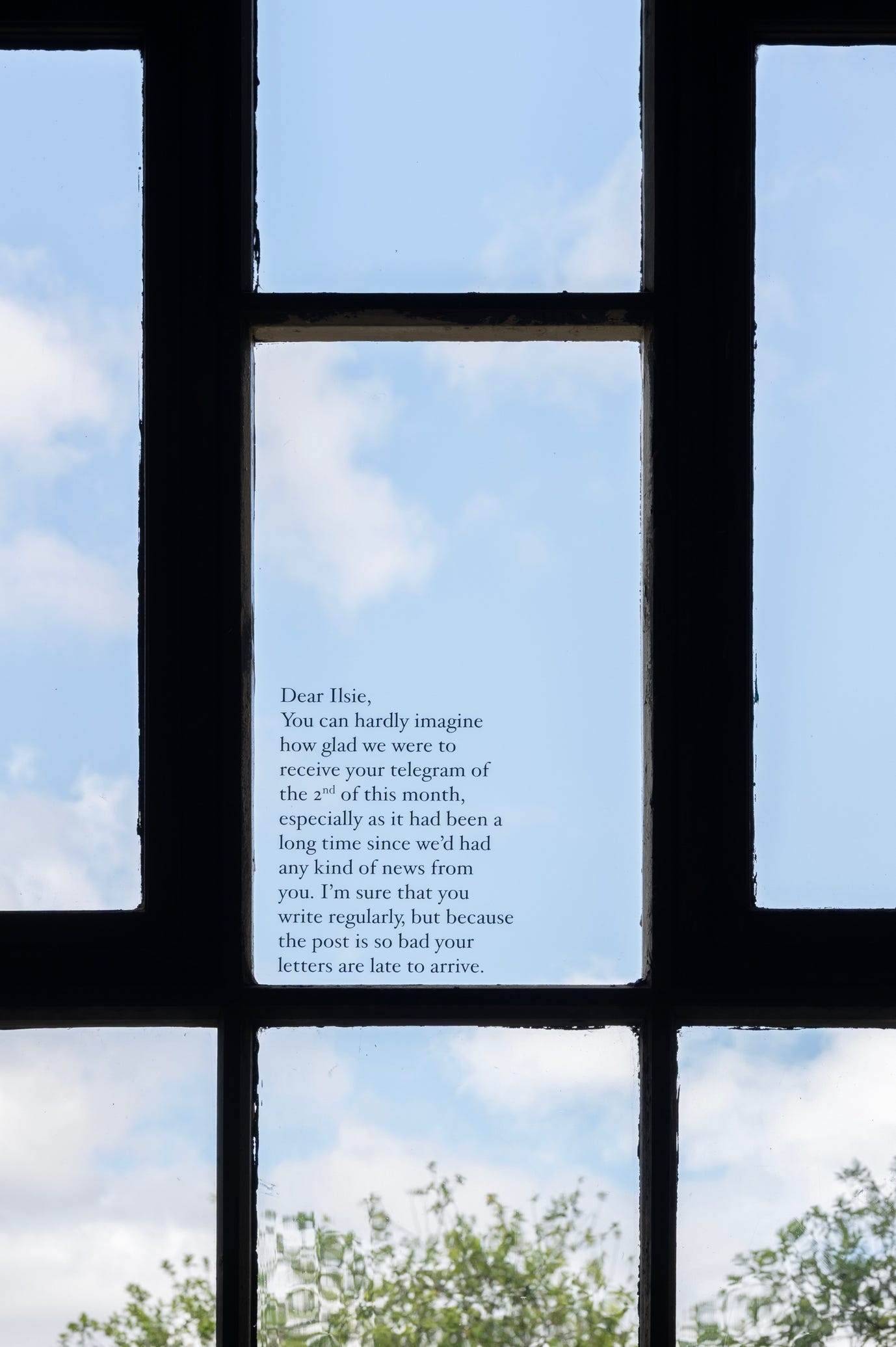

My contribution to the exhibition was a series of nine of the two hundred and something letter-excerpts translated in the book, displayed as vinyl text on the windows. In the book I chose and translated parts of the letters that were about the business of letter-writing – people thanking people for letters and parcels, people commenting on how long they had taken to arrive, expressing relief to get news, apologising for taking a long time to reply. The nine here were those which began ‘we were glad (or delighted, pleased, etc.) to get/receive/hear from…’.

I wanted it to be similar enough to the book that I wasn’t muscling in on the visual artists’ territory, but also a translation of the book into a different mode, and perhaps also to make clear to myself what I thought I was doing with the book more generally. At the opening I suddenly began to worry that people would only read one part of the book, which I had conceived as a whole, each part working against, or altered by, the others. I wanted the letters to be anonymous, not tied to specific histories, and I wanted to let the sense of an unfolding story come to the surface while frustrating the desire to follow any given arc to its end. But I also included short biographies of the writers and recipients of the letters at the end of the book. I wanted the letters to be repetitive, boring, unsensational, but knew that there was no way of keeping out what people already knew. I wanted not to be present, but knew that that was a fiction – but also knew that the fiction was a necessary one. The essay, or ‘notes’, at the end recorded some of the experience of the residency, my aims, my feelings of ambivalence and so on – that is, noted this presence; but I hoped that all that had gone before would not be marked in that way, would be clear and simple.

The idea for the installation had been that visitors would encounter the letters as they walked between the other works; I’d initially thought about putting them on the white pillars in the centre of the space. The curator, Paula Kolar, helped me make it work, doing trial versions and checking font sizes for viability and legibility; she also noted that the text wasn’t always visible against the high bank of trees outside to the west. It was only when I got there and was choosing which panes to use that I realised that this was a good thing – I had wanted the letters to become suddenly and surprisingly visible, and the setting meant that only at particular angles was the text legible at all.

Their appearance also changed considerably with the weather and as the sun moved around the building, fading slowly into the late dusk of the opening. The year before, I had, on my second trip to the archive, decided on a project about the weather; I ended up abandoning it a couple of months later and turning to this one, but I was glad that some of those ideas (which I also picked up in the notes, particularly in a discussion of Harun Farocki’s Images of the World and the Inscription of War, about aerial images of the Auschwitz compounds taken by the Allies on a rare day without cloud cover) were once again part of the work. While one of the central ideas of the book and project was ordinary uses of language and ‘phatic’ language, language that communicates feeling through its existence and its following of formulae and not through its semantic content, I was also very interested in the ideas of temporal dislocation and delay that came up so often in the letters, which was partly a feature of the medium and partly a result of war-time logistics – things took long enough to arrive, if they ever did, but even longer if you made your letter in some way hard for the censor to read, through bad or elaborate handwriting or by writing in a language that wasn’t the primary working language of the censorship office it had to pass through. It was pleasing to find the building and the trees creating these kinds of delay in the gallery. The way the text would suddenly come into focus, I realised, also mirrored the experience of going through piles of handwritten letters in the archive which required patience and frustration to decipher and suddenly coming across one that is typed or printed, and it is immediately legible.

So, on the one hand the viewer had to move to be in the right place to read the texts; but on the other, if they found themself in the right place, the text was there to meet them, even if they had not been intending to read it – it would happen to them willy nilly (or so was the idea). As I mentioned above, part of the residency brief was to deal with the contemporary relevance of the archive, and to understand how the Holocaust has shaped our present understanding of genocide. I wrote before about having applied to do the residency as a way of making use of my skills in the context of the present genocide in Gaza. What I produced is of such oblique use in this context to be basically irrelevant, although some of the thinking that went into it was directly drawn from present questions to do with the representation of suffering, the use of emotive language and images, the role of chants and slogans and how we should understand what they mean, the value of explicitness in political speech and art. I came away feeling I’d failed – which seemed to have been probably necessary all along – to create both a meaningful response to the personal archives of refugees from the Holocaust and a piece of work that would be useful and good in the present. As many of us have, I’ve allowed myself to feel despondent and to find it hard to work at all when thinking about my powerlessness in the face of killing, destruction, forced displacement and forced starvation, but have felt that that feeling was also cowardly and self-indulgent. At the same time, any disciplined commitment to a long-term project can feel like an almost callous abdication of an urgent responsibility to produce something for now – but what?

The other day I went to a gig in which one of the pieces had been written by my friend and collaborator, Grace Connolly Linden. It was a poem that she had scored visually, which was then interpreted by the group. The text was read through a megaphone and a range of sounds were made around it of increasing violence. My impression had been that the text and the sounds were in some kind of tension: I wasn’t able to pick out or concentrate much on the words, but it began ‘I have tended to forget, like a garden’ and I heard mentions of flowers; a friend said it had sounded ‘pastoral’. I asked her to send me the score.

When I read it, I found it was in fact about Gaza, specifically about the work of mourning and response that was possible from afar. It was nothing like anything else I’d read or heard on the theme, which has often taken the form of a kind of self-reflexivity – what can I, or poetry, do? – or else simplicity, sometimes to the point of sentimentalism or sententiousness. This was complex, unafraid to be oblique and difficult. It didn’t condescend by refusing its subject all of the resources of poetry, instead, drawing on the history of literature of lament and complaint (Virgil, the Book of Job), mustering these resources as a kind of offering. The flowers were from Louis Zukofsky’s “A” (‘To-day I gather all red flowers’). It was rich, polyphonic, multimodal, sensory rather than intellectual or moral. And it was beautiful, and full of feeling – about feeling – but not in the least sentimental; clear about what it despised but not reproducing the sensationalism of its antagonists. As with Chebo’s drawings I immediately saw how narrow my previous understanding had been of the form that art that is about, and against, atrocity can take, and how restraint and austerity can be a form of cowardice. The text of part of it is here; the whole score is not available to read anywhere yet, but I hope it will be soon.

Grace has also organised the printing of a fundraising t-shirt, designed by Aisha Farr with Angela Shackel, using the refrain of a miners’ union song, with a limited range hand-dyed by Grace, with all of the proceeds going towards the legal costs for people arrested at Workers for a Free Palestine demos. You can buy it here. (She asks me to add that there is a risk of certain sizes and colours selling out before we have had a chance to update the site – sorry!)