Bill Viola/Michelangelo

Bill Viola/Michelangelo, Royal Academy, 26th January-31st March 2019

Bill Viola, a pioneer of video art and one of its most respected practitioners, is praised for dealing in questions on an existential scale in an art world wary of universalism. This, along with his unembarrassed interest in addressing, and producing, emotion, he shares with Michelangelo, according to the curator of the Royal Academy’s foolhardy but illuminating current show, which pairs a selection of Viola’s installations with Michelangelo’s drawings in a ‘conversation’ on the nature and fate of the soul.

Viola’s interest in Renaissance art began in the 1970s when he was an apprentice of sorts at a studio in Florence, but changed gear around 2000 with The Passions series (represented here by Surrender, 2001), and as such his spiritual ideas, a familiar blend of world mysticisms, have latterly come to be expressed in a distinctly Christian visual grammar. It is the structural features of Renaissance art—its spatiality, or the powerful hold devotional paintings have on a viewer’s attention—that Viola wants to recreate, decoupled from their content, through techniques such as slow motion, and sheer scale.

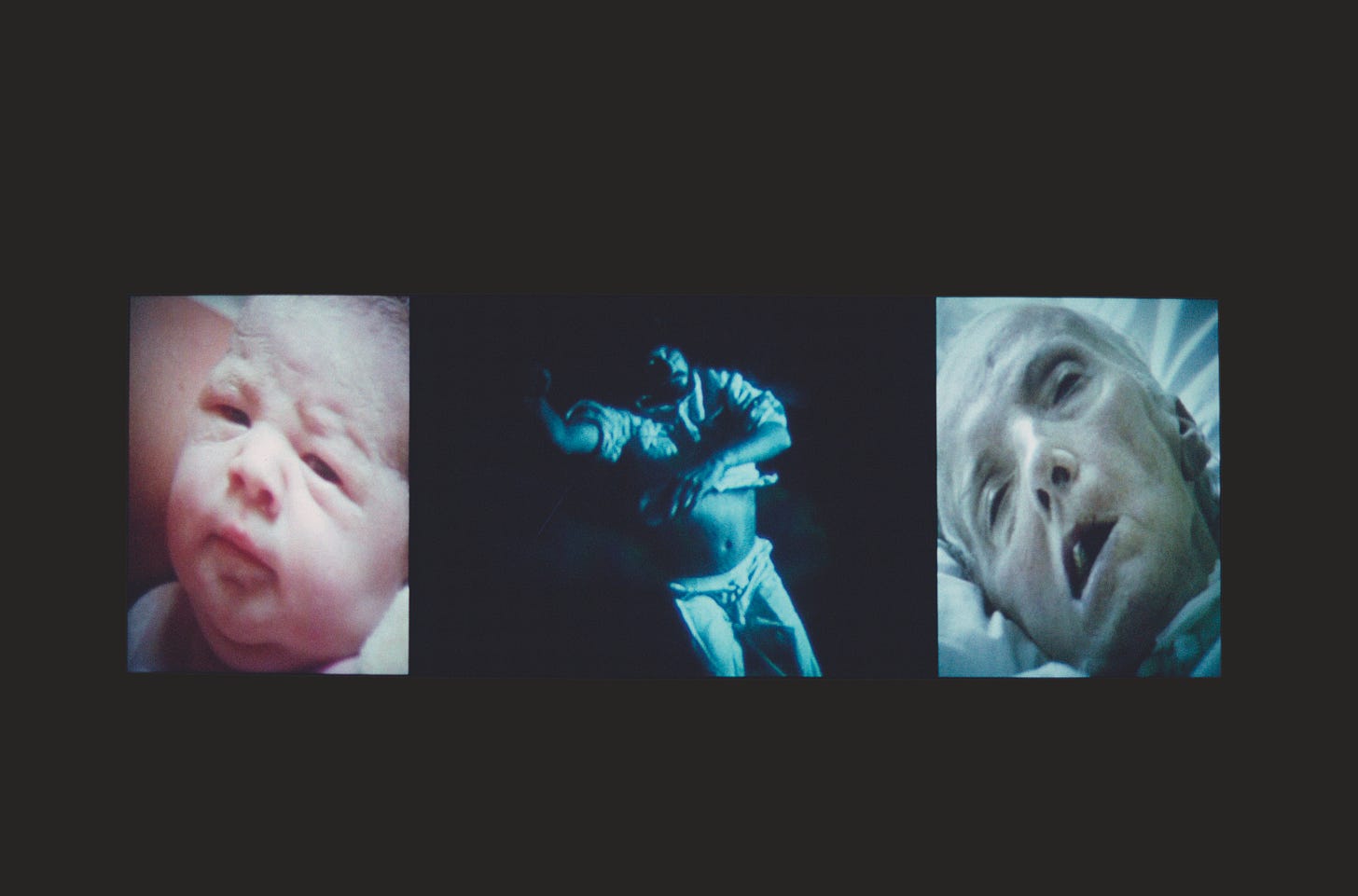

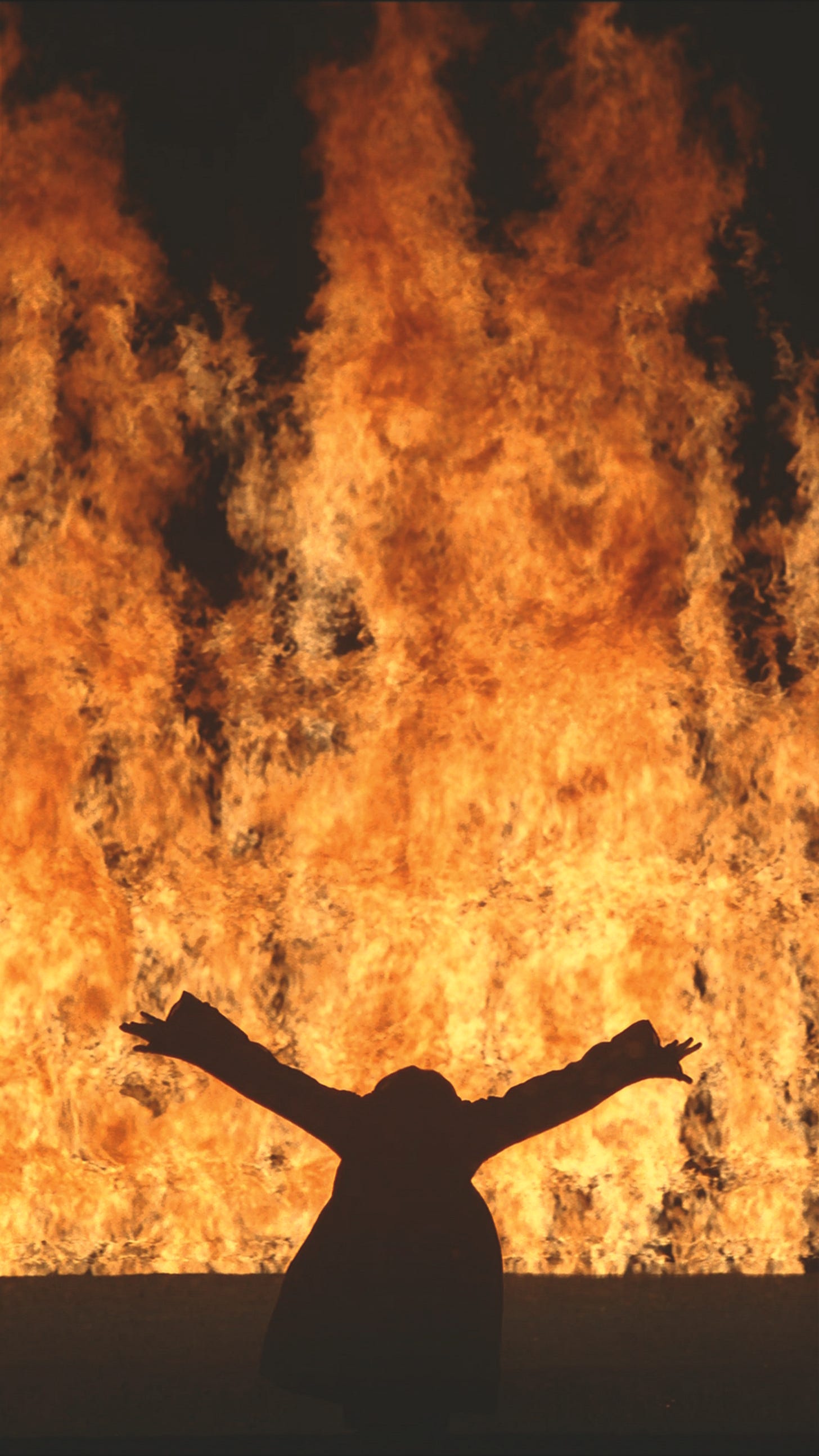

The installations at the RA are room-sized and spectacular. Bodies are suspended, often in water; asleep, adrift, sometimes clothed, sometimes naked but almost always alone: the individual, for Viola, lives in irredeemable isolation. Two earlier works set out his beliefs: in Slowly Turning Narrative (1992), a rotating mirror reflects a collage of brief colourful scenes onto the viewer and a voice intones, separately, an undifferentiated list of ‘states of being’ (‘the one who sucks, the one who cares...’) encouraging what the catalogue calls ‘a powerful sense of dualism’; in Nantes Triptych (also 1992) the centrepiece depicts life as a ‘mysterious interplay’ between body and soul (alongside a birth and an old woman, breathing through a tracheostomy, with the merciless flickering implication that she is all but waste matter). Viola is good at suspense: there always seems something about to happen, however slowly, and so attention is harnessed, not for attention’s sake, but for the sake of a body falling into its own reflection (Fire Woman, 2005), or being born, or indeed dying. One watches, and is moved, almost against one’s will.

The Triptych is one of the works sharing a room with Michelangelo, matched according to theme (here, mortality). The differences in medium make it fairly easy to avoid comparing them as artists in a narrow sense; but the conceit makes it harder to avoid comparing them as men formed by and working with the ideas of their times, and it is here that Viola’s relative impoverishment is clear. Michelangelo’s spirituality is shown to be historically particular; his Neoplatonism as well as involvement in the suppressed Spirituali movement are over-emphasised in the exhibition commentary. Viola’s ideas, and the characteristic vagueness with which they are expressed, belong equally to their time, yet escape this treatment. For Viola, particularity is a postmodern trap; thus, too, Giotto’s frescos ‘are the first movies’: there is no joy in the materiality of a given medium, and most matter is a kind of prison, a word Viola uses of both bodies and paintings.

Critics of Viola are accused of snobbery, or emotional prudishness. He is certainly an easy target thanks to his popularity, the exaggerated institutional prestige, and the lack of irony or play or anything that might temper the grandiosity, as well as the pretentiousness and contradictions of his statements on spirituality. There is, currently, a great appetite for the kind of questions Viola is asking but distinctly less for the particularity of the demands made by concrete answers, such as those of Christian doctrine, which is why his syncretic mystical pick-and-mix, alongside the high emotion of the installations, works. The effect is visceral and content-free, a performance of profundity, with interpretation a matter of context: The Messenger (1996) – in which an abstract shape in water rises to the surface, becomes more and more clearly a naked man who breaches, breathes, sinks back down – was created for Durham Cathedral, and seen there it would gesture more obviously to baptism, the repeated surfacings taking on a liturgical urgency. In a gallery it loses that specificity, and the uncanny blankness of the young man’s expression suggests that life, whatever it is, is absent here.

And where the context is the precision of Michelangelo’s faith, even the emotional effects are dampened. Surrender (2001), a vertical diptych in which reflected portraits of a grief-stricken couple become distorted through the rippling effect of the water they surrender to, is mesmerising when viewed alone, and manages to address conceptual issues of mediation with a lightness of touch. Flanked by Michelangelo’s late drawings of the Crucifixion, however, it becomes merely a distraction from their more pressing depictions of human anguish. The suggestion that they both use degrees of definition (Christ’s body seems to dissolve into the wood of the cross) to treat the departure of the soul from flesh is either blasphemous or banal.

The history of visceral emotional response belongs to devotional art, but also to genre cinema, and the obscenity of works like The Messenger is not that they show nudity but that they demonstrate an almost blanket contempt for the human body, using it as a means to an end. Opposite Man Searching for Immortality/Woman Searching for Eternity (2013), where a naked couple, projected onto slabs, look with torches for signs of disease or defect on their ageing bodies, are Michelangelo’s drawings for Tommaso Cavalieri. These are virtuoso performances depicting the consequences of obeying lust as opposed to divine love, of not differentiating, that is, between good and bad ways of living in one’s flesh. The Children’s Bacchanal is shocking: chubby infants strain in pursuit of senseless pleasure, pissing into vessels others drink from (‘strain’, ‘piss’ and ‘drink’ are all among Slowly Turning Narrative’s ‘states of being’). Viola glosses the climax of Fire Woman as triggering ‘the realisation that the body’s desire will never again be met’. In attempting to meet merely bodily desires for art, Viola’s work exposes their insufficiency.

March 2019

(Images courtesy Bill Viola Studio; photos: Kira Perov)