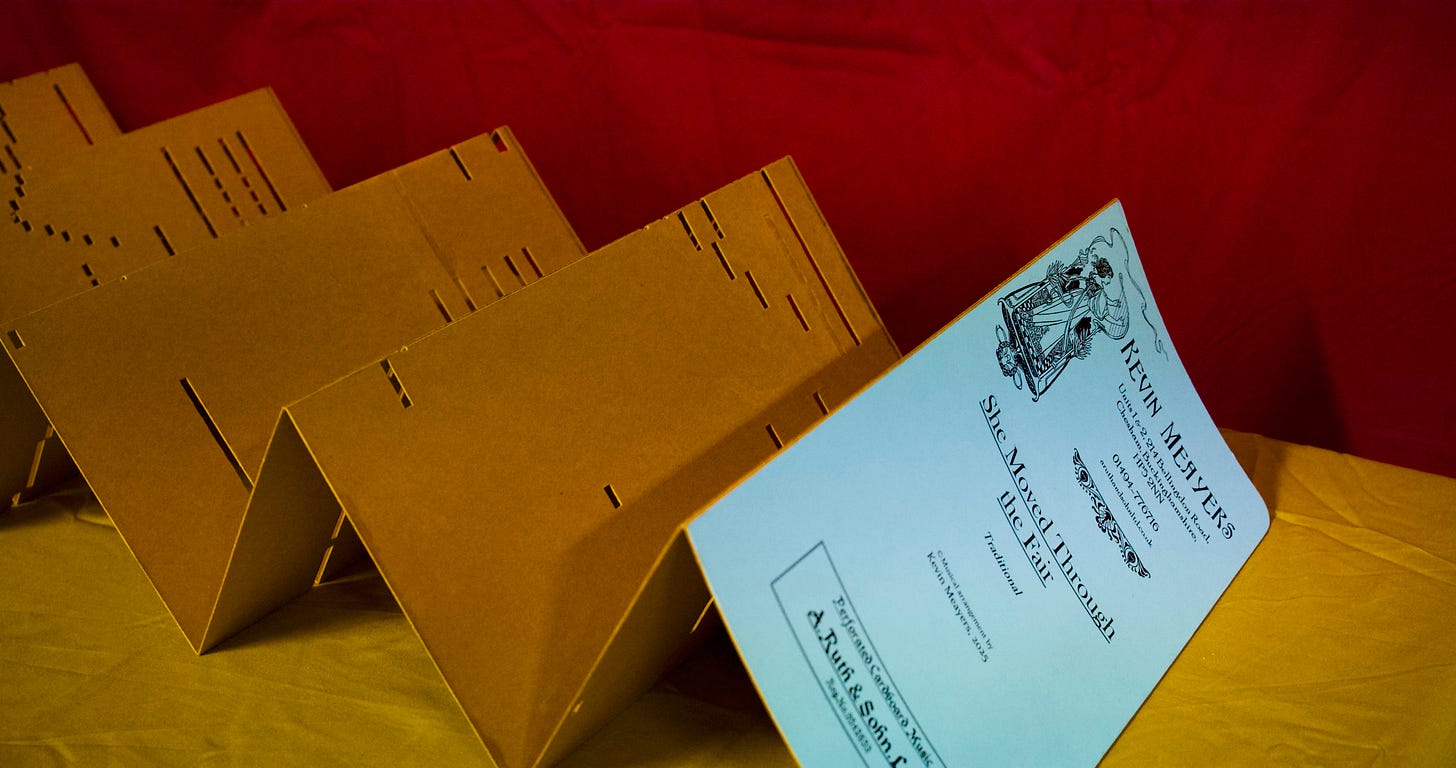

This is just a short post to flog a pamphlet (& project) I am part of. The pamphlet is called ‘She Moved Through the Fair’; all of its contents are in some way a response to the song (sung here by Anne Briggs), although the directions everyone has taken ended up diverging, so far so that at one point I worried that it, and especially the launch event last Friday, would come across a frustrating jumble. We began by talking about the song, in particular, the figure of the ghost lover, on the one hand, and on the other, the social history of the fair. Quite early in the project a few of us went on a tour of the Metropolitan line organised by my friend Lydia Heaton, which ended at Amersham Fair Organ Museum on one of its open days, and this was especially influential on the project – the loose group that we are is now called The Fair Organ, and one of the objects at the launch was a perforated card song book of ‘She Moved Through the Fair’ arranged for mechanical organ that George Townsend, one of the group, commissioned of an organ maker, Kevin Meayers. (George also made a film of the song being played on a fair organ.)

My contribution is a sequence called ‘Ghost Sonnets’, which is a go at thinking through the idea that the British are peculiarly interested in ghosts, haunting, possession – especially places and landscapes. A French friend confirmed this for me – she had moved to the UK because she said that nobody in France would supervise a PhD on ghosts – and made the convincing claim that it was based on latitude, which I then found elaborated in Peter Davidson’s The Idea of North (‘Ghosts in Europe are northern. It is panic terror that belongs to the south: possession at noon, sudden fear born from heat haze, and empty tracts of hillside that are suddenly inhabited. […] But the revenant narrative is essentially of the north, and is a product of the occluded weather and broodings upon the fate of the dead.’) – as well as his Arctic Elegies. I tried this idea out in Brittany last November and everyone claimed that the French do believe in ghosts, and to prove it brought out a French monograph on haunted houses. When I read it, it turned out that all of the case studies were English people having seen ghosts in English houses. (For the two weeks I stayed there I kept saying to myself and others that the house, an old manor house, felt unusually unhaunted; on the last night I was kept up by a knocking sound against the wall by my bed, which I couldn’t help but believe was revenge.)

This idea of haunting then – the national obsession with ghosts, fairies, possession, all the neo-folklore stuff, the haunted houses, the ghost stories – has something to do with geography, with latitude and meteorology, but also seems to be a convenient way to deal with, or release the pressure of, the unease of finding oneself or the nation in a relation of non-supernatural power – a way of making manageable and perhaps also eroticising an unease to do with, for instance, empire, class, and so on. And the convenience of this began to unsettle me – that the UK above all things does not need another way to understand itself as exceptional, somehow peculiarly haunted, and does not need any more self-regarding nostalgia, any exceptionalising of its housing stock and land, even of a critical kind.

At the same time I find it hard to fault someone like M John Harrison, who makes of the (in this case specifically) English weird something that does seem productively to gnaw at the roots of the exceptionalism itself, most explicitly in the recent story ‘English Heritage’, and in a slightly different way in The Sunken Land Begins to Rise Again (the only good novel about Brexit?), but also the post-Thatcher 90s novels set around the border of Yorkshire and Lancashire.1 The reason I think so much about all these English and Welsh and Scottish and Anglo-Irish ghosts, Fitzgerald, Spark, Bowen, Mantel – Aickman – as well as M R James and all the rest – is because I feel at home with them, of course. But then I worry that this is a guilty pleasure, a way of escaping that masquerades as a kind of critical engagement.

All of this is something like the argument of one of the poems in the sequence, and feeds into another, which is about the popularity of homoerotic heritage TV/film in the 1980s. They’re also about my own susceptibility not just to literary depictions of malign supernatural forces but also to the fear of them, and then other ideas and things that I needed in some way to exorcise. Robert Aickman, the writer of ‘strange stories’ (and founder of the inland waterways association) whose story ‘The Swords’ was another important starting point for the project – fairs, disembodied hands, (homo)sexual menace – liked to make the point that the successful ghost story was ‘akin to poetry’ – specifically in ‘deal[ing] with the experience behind experience: behind almost any experience’. (He also claimed that England ‘is generally regarded as the metropolis of the supernatural, as of lyric poetry.’) I wanted to see if I could – like Hardy or Charlotte Mew, or indeed Keats – write poems that were ghost stories. I’ve included one below; you can buy the pamphlet here. In it are also interviews with Kevin Meayers and with the historian Sally Alexander, who wrote a pamphlet on St Giles’s Fair in Oxford, and poems by Hugh Foley, Grace Connolly Linden and Aisha Farr. There is also an insert made by the poet Edwina Attlee of an imaginary exhibition of fairings based on Southwark’s Cuming collection, etchings by Daisy Nutting, and endpapers and a essay by Angela Shackel. And two stickers! If you’re in London, I’m reading the sequence along with other things at Hard Work, at Ryans N16, 4pm tomorrow (Sun 2nd March) – £5/pay what you can, cash on the door.

Truly one of the canonically haunted places in the UK – as is Hilary Mantel’s Glossop and North Derbyshire more generally, I think, although I don’t know it well.