On Rohmer and Being Wrong: Part 6

Eros, control, not getting what you want

In the last post I mentioned the homoeroticism of Rohmer’s films, possible only in a context in which straightness is a given. Rohmer often depicts friendships – between women, between men, between men and women – that are eroticised because there is something that prevents them sleeping with each other, that keeps each at a distance. Sometimes something happens to remove this barrier, and this is shown to destroy the force that kept them together, such as in Love in the Afternoon, where Chloé is naked on the bed waiting for Frédéric, and he finds that he does not want her, he wants what she represents, which is the other and which is fantasy incarnate. Precisely because she is other, she is not in fact right for him, and precisely because she represents fantasy, the possibility of consummation transforms her into something he no longer wants.

Of Claire’s Knee, Rohmer has said Claire ‘she stands for an attraction that is purely erotic, in the most refined sense of the word’.

It’s a common enough thing in men: the contradiction—even within desire itself—between what is purely desired and only desired, and what is possessed. The object of desire is not necessarily the object of possession. That’s what I was interested in showing. […]

Ultimately, touching her knee is simply a way of being able to say “I touched it,” like children when they’re playing tag . . . Possession for him adds nothing to desire. On the contrary, his desire feeds on the absence of possession. That’s what satisfies him. It’s not an unusual state, and there’s nothing morbid about it.

Perhaps in 2012 it wasn’t clear to me how much the absence of possession structured my own erotic life. The two months of fevered Rohmer-watching came after a significant break-up, the end of what is still the longest relationship I have had. A factor in the break-up was that I had fallen in love with someone else. It was an open relationship and so in principle tolerated sexual and romantic relations with other people; but what had attracted me to this new person, and what was all-consuming about the attraction, was his unavailability, an unavailability that meant that I was free to make him into a perfect Other, someone whose way of being was completely and incomprehensibly unlike mine, whose approval I could always seek and never fully obtain. I was simultaneously fully aware that this was what was going on and fully signed up to the idea that I did truly want what I claimed to want to myself, and that the force of the attraction – and affection between us, because we were also, if in a very troubled way, good friends – would somehow transmute the desire for the unattainable into something real – love in a real sense – in the moment of its attainment. Perhaps for that reason I resisted the Moral Tales, with the men resisting the woman who represented the other, who represented possibility itself, for the women who represented the status quo.

The status of the two women in these films is ambiguous. They represent for the male protagonist a way of life that is other. But, as we know, their non-conformism is a conformism of a different kind. We are left with the sense that Rohmer disapproves of their way of life – at the ends of the films they are left naked on the bed, on the roadside, on the beach in a failing marriage – but it is they whom the film has depicted as more real than the woman to which the man returns, who seems often as much an incarnation of a different kind of fantasy, as if the man is deciding not between fantasy and reality but two opposing ideas that he is projecting on the two women in turn.

The most schematic example of the story in which possibility kills desire is in the second of the three short films of Rendezvous in Paris (1995), ‘The Benches of Paris’. A young woman who lives with her boyfriend is in love with a second man, whom she meets on park benches in Paris, and never inside, either his flat – which is in the suburbs – or her boyfriend’s. Their relationship escalates to the point that she suggests that they book a hotel in Paris together and pretend to be tourists while her boyfriend is away for the weekend. But when they arrive at the hotel they see the boyfriend enter with another woman. Rather than be glad of an excuse to leave the boyfriend for good – she has spent the film talking about how boring he is, how she is on the point of leaving him – she is distraught. And rather than being free to love the second man, she now no longer has any need of him.

The woman has been shown in the film to have very definitive preferences, like many of Rohmer’s protagonists. In a park she insists they move the bench out of line to sit against a tree, for example:

His characters say so often ‘j’ai horreur de…’ that for a while I forgot that ‘I have a horror of’ is not really used much in English (the subtitles usually translate it as ‘I hate’, as here:

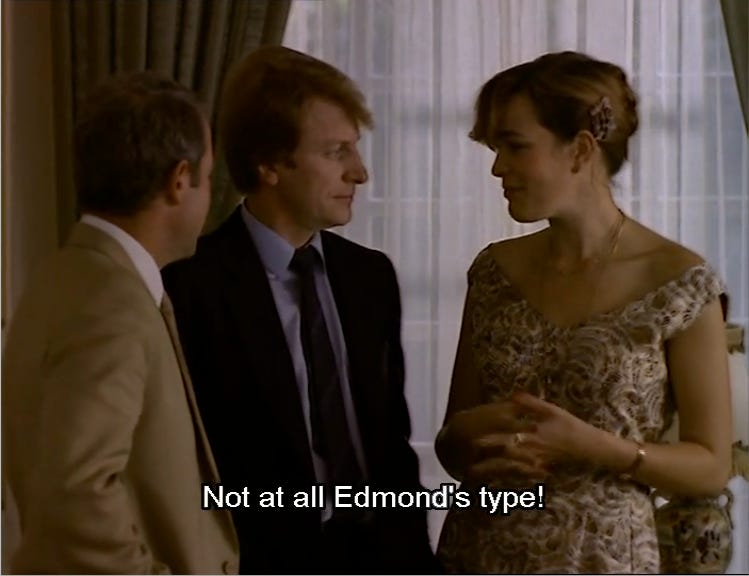

Similarly, there is much talk of who is or isn’t a given character’s ‘type’:

Rohmer is not against types, as I have said. He claims not to have a type of actor and to use actors who look very different from one another, but it seemed to me at one point that all his female actors had uncannily long torsos – exaggerated by the fashion for bikinis where the top is high and the bottom low, but nonetheless noticeable, particularly when it is broken, for example by Amanda Langlet, who is unusually stocky. The films show relationships that are doomed because the characters are not each other’s type – they are oddly matched, like Frédéric and Chloé, or the two men that Félicie bounces between in Tale of Winter as she waits for Charles, her true love. What Rohmer is interested in is when characters assert their preferences as a form of self-deception, of creating a kind of identity for themselves that is false and which limits their vision; or else when meddling friends try to persuade characters who are unsure of their identity what their ‘type’ is against their own sense of uncertainty and openness to discovery.

At the end of ‘The Benches of Paris’ the young woman, in parting, tells the confused lover he is not always to believe what she says. All along she has known that what she claims to want and what she actually wants is different; but only in this moment is she in a position to express it and to act on it. Sometimes these moments, which seem like manipulation, come across as somehow very ‘French’, part of an elaborate game-playing in relationships where you don’t say what you mean, as practised best by Sophie Renoir’s Léa in My Boyfriend’s Girlfriend. But these games are also a matter of self-protection, the self colluding with itself in a deception aimed at another and the character in order to save face, to avoid humiliation, like Béatrice Romand’s Sabine in The Good Marriage telling the man she had been pursuing, when he rejects her, that she doesn’t really want him anyway (which – in fact – is true: she was put onto him by her friend).

Rohmer’s characters are, for the most part, very unwilling to give up control. It is partly for this reason that there is very little sex in the films, and what sex there is is often interrupted or in some way shown to be not ‘real’ sex (Haydée making eye contact with Adrien while in bed with Rodolphe), with the great and, when I first watched it, shocking exception of the opening sequence of Tale of Winter. These are characters whose defences are up, and this is part of their mistake. As I suggested before, I don’t think Maud is wrong when she suggests that the protagonist’s lack of openness and spontaneity is ‘not very Christian’. What many of Rohmer’s protagonists lack, at least the ‘masculine’ ones (including Pascale Ogier and Béatrice Romand’s characters, which I plan to write about in the next post), is a grasp of the reality of the other.

*

I moved to London because I wanted to fall in love. Or rather, because a friend said I wouldn’t fall in love until I did; at least until I left Oxford. But when I moved to London, I found it curiously unerotic.

I had previously associated London with a kind of openness to the world that I felt I was lacking. I heard stories of ‘messy’ colleagues, who went out in London, who had coke habits – lives which seemed full of risk and interdependence. Moving to London was a disillusionment. I found that the parties and the drug-taking were a way not of losing control but gaining it, controlling the possibility of things happening by determining in advance what would happen, guaranteeing a particular kind of pleasure while never seeming to have that much of a good time – about the same amount of a good time as one might get from a good pastry or ice cream, all the everyday indulgences that structure the life of youngish people in London. And those who did seem to seek a kind of abandonment or wildness sought it not as a way to be porous to others, rather instrumentalising them in their pursuit of an experience outside of the self, the abandonment a way of closing oneself off from the world.

I found myself looking for people who seemed to represent the kinds of openness that I meant. Who were spontaneous, unpredictable, trusting, willing to take risks. I don’t mean that in a normal way – there is a lot of risky behaviour in London, far more than I was used to, the cycling for instance. But all of the risk is oddly goal-oriented. I began to refer to this openness to the world, this porosity to others as ‘danger’. My housemate suggested the word ‘play’. Both danger and play seemed in a way wrong for what I meant, as did the words eros and sex, because when I said there wasn’t enough sex at a party, I didn’t mean this literally – rather that nobody was lacking some kind of shell. I wanted to feel that something was on the line, that something could happen.

I read Adorno’s essay ‘Sexual Taboos and the Law Today’ in a reading group, in which he talks of the desexualisation of sex. I came away telling everyone how much I felt that sex, in London, had lost its sexiness. Nowhere did this seem more the case than on dating apps, which were full of people pursuing very specific desires or kinds of relationships, whether marriage (Hinge) or kinks, roles and configurations (Feeld). People were able to name their desires and wanted others to be able to do the same, in ways that seemed to me to ignore not only the psychology of the erotic, but also how language, or rather, as it is referred to on the apps, ‘communication’ works – as if sex were a matter of naming a specific want and having it fulfilled, as if communication consisted only in the exchange of propositional statements and not tone, gesture, silence, everything that happens underneath and against speech.1 As if one could never find oneself unable to say what one wanted, either because one didn’t know yet what one wanted, or didn’t want to face up to knowing – or else because the social context made it impossible, the humiliation or awkwardness or impoliteness involved too great; as if there were no such thing as tact, discretion, saving face.

A friend who is newly on the apps was saying that she couldn’t understand how one could work out if there were chemistry in the context of this kind of date, which ruled out in advance the kinds of ambiguity and uncertainty necessary for the certainty of attraction. I saw a meme which suggested that it was a cliché of right-wing Substack to go on about how dating apps have killed romance. And while I have often felt that I could never fall in love through an app – indeed I have often thought I could never fall in love from any context where one goes explicitly to meet people, like student union LGBT socials – I know that so many people do manage to fall in love through apps; and chemistry, some sort of psycho-physiological connection to an embodied person, a kind of grace, I know that I have experienced it, even on dates with people I’ve met on the apps. Type, or something like it, is real. But eros seems possible only when it somehow goes against the grain, against expectation, or perhaps better, when it comes from outside of oneself.

I have often criticised accounts of eros which make a big deal of surprise, because I have never been surprised by desire: it has always occurred in situations that seem to me completely predictable, like that with the friend who I watched Rohmer with in 2012. I know well what I want, which is intense intellectual relationships with friends who are married, so that the pleasure of non-consummation can last a lifetime. But in a way the two are the same account, from different sides. One way or the other, eros is about not getting what you want.

***

I haven’t had time to integrate it here but really enjoyed reading this essay on Rohmer by Leo Bersani and Ulysse Dutoit (DM me for a pdf). The next and penultimate post will be about actually getting what you want.

This week I read Sam Kriss’s virtuoso essay on the philosophy of time via rewatching Girls – which, in a paragraph, describes and explains the economic and sociological factors behind sex having lost its sexiness, the Shoshanafication of personal identity, that I have spent months of my life writing about – and was struck by the fact that my first Rohmer season had coincided with watching, with almost the same people, the first season of Girls. Are we all at it? returning to 2012?

Rohmer talks in this interview about the difference in style of the Tales of Winter and Summer, and of Springtime and Autumn, the conversations of the first filmed at an angle because you can trust the characters to say what they are thinking, the conversations of the second filmed from the front because you cannot, and so you have to watch them carefully.